Canadian customers finalizing 2026 budget: Check out our 100% Canadian owned and operated reseller, Canadawide Scientific.

Why bats & tea?

Tea is a vital crop grown in large plantations across tropical and subtropical regions. The top tea producers—China, India, Kenya, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam—generate 80% of the world's tea. Sri Lanka, a major player, introduced tea in 1839 and now ranks as the fourth-largest tea producer and second-largest exporter, with plantations covering over 200,000 hectares.

However, tea cultivation (like crop production worldwide) faces significant pest-management challenges. Heavy reliance on chemical insecticides poses environmental risks and has led to chemical pesticide resistance. Because of these adverse outcomes, Integrated Pest Management (IPM)—a practice combining physical, cultural, biological, and chemical pest control methods—is becoming increasingly popular.

One key aspect of IPM, biological control, uses natural predators to manage pest populations. Enter bat biologist Dr. Tharaka Kusuminda, whose research explored the potential of bats as natural pest controllers in Sri Lanka's tea plantations.

Project objectives

In 2021 and 2022, Dr. Kusuminda and his research team conducted fieldwork across 11 tea plantations representing various ecological zones, including low-country wet zones, mid-country wet zones, up-country intermediate zones, and up-country wet zones. Kusuminda chose each site to illuminate bat diversity across different elevations and habitats.

Research objectives included:

Strengthen the existing bat call library and make it publicly available. All bat species recorded in Sri Lanka can also be found in many parts of Asia.

Assess the bat species diversity along an agroecological gradient and quantify the temporal activity pattern of sympatric species.

Examine the impact landscape features have on bat activity, with a focus on plantation size, surrounding habitat, and availability of nearby bat roosting sites

Build capacity of field assistance for continued long-term monitoring, including operating passive acoustic bat detectors and processing and analyzing data.

Create bat acoustic baseline data and assess the effect of anthropogenic pressure on species distribution and abundance in tea plantations to document trends and provide conservation recommendations.

Materials & methods

Setting up the fieldwork

To begin, Dr. Kusuminda and his team paired Android mobile devices with Echo Meter Touch 2 PRO active bat detectors to identify bat flight paths at the plantations. They then set up two passive Song Meter SM4BAT FS recorders equipped with high-sensitivity SMM-U2 ultrasonic microphones at each site—one near the plantation edge and the other towards its center. Recorders were mounted on shade trees at least 500 meters apart, and microphones were positioned 1.5 meters above the ground to avoid noise from the tea bushes and soil.

Recording bat activity

For 24 hours, recording took place from sunset to sunrise, ensuring the full range of bat activity was captured. ARUs were configured with specific settings, including a gain of 12 dB, a sample rate of 500 kHz, and other parameters fine-tuned to catch the bats' high-frequency calls, including:

16K high filter: off

Minimum duration: 0.5 ms

Maximum duration: none

Minimum trigger frequency: 10 kHz

Trigger level: 12 dB

Trigger window: 5 seconds

Maximum length: 5 seconds

Processing and analyzing the data

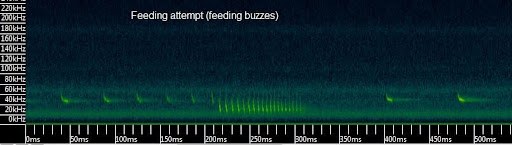

Back in the lab, the team processed the data using Kaleidoscope Pro Sound Analysis software. In the initial stage of analysis, noise sound files were removed, and a whopping 26,480 bat sound files were separated during batch processing. The software's Cluster Analysis function was then used to group similar bat sounds. To identify individual species, the team measured key call parameters, including:

Minimum frequency (Fpmin)

Maximum frequency (Fpmax)

Frequency at maximum energy (Fppeak)

Call duration (Dur)

Time between two calls (TBC)

Bandwidth (BW)

Project outcomes

Create a bat call library

The team successfully recorded echolocation calls of 27 bat species, representing eight bat families in Sri Lanka. The call characteristics of these bats are being prepared for publication and will be made publicly available through Dr. Kusuminda's website. This comprehensive bat call library will provide a valuable resource for future research and conservation efforts throughout Asia.

Understand species richness

Researchers identified at least 20 different bat species within Sri Lanka's tea agroecosystems. Twelve of these species were confidently identified by their unique echolocation calls, and the remaining eight species were identified by overlapping call patterns grouped into sonotypes.

Two species grouped into sonotypes, Pipistrellus ceylonicus, and Miniopterus phillipsi, were identified through capture in mist nets. In total, 14 species were confirmed, representing all seven insectivorous bat families in Sri Lanka.

The highest bat diversity was found in Kotapola's tea plantation (elevation 206 m), with 12 species, while the lowest was in Nuwara Eliya's high-elevation plantation (elevation 2138 m), with only four species. These data suggest that elevation affects bat diversity, with lower elevations generally supporting more species.

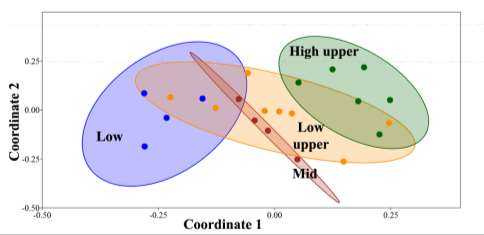

Understand insectivorous bats' community composition

To study their distribution, bats were grouped first by ecological region and second by elevation. Results showed some overlap between insectivorous bat communities in different regions; however, significant differences were observed between low-country wet zones and up-country wet and intermediate zones. Similarly, bats at high elevations had distinct communities compared to those at lower elevations.

Understand temporal activity patterns

Echolocation calls of 15 insectivorous bat species were captured, revealing three prominent activity peaks: just after sunset (6-7 PM), around midnight (1-2 AM), and just before sunrise (5-6 AM). Activity was lower during the late evening and early morning hours. Bats at low and high elevations had similar activity patterns, peaking after sunset and before sunrise. However, low elevations saw higher overall activity levels.

Different bat families showed varied activity patterns. Those adapted to cluttered environments had unique peak times, and others that prefer edge habitats increased activity after sunset, with some staying active longer.

Understand bats associated with tea agroecosystems

All but one recorded bat species were found foraging within tea plantations. Results highlighted nine species actively hunting, representing open habitat molossids and emballonurids, edge habitat vespertilionids, and clutter-adapted rhinolophids. Hesperoptenus tickelli was the most commonly detected species found in all ten surveyed plantations.

Build capacity in the field

Field assistants Chamara Amarasinghe, Mathisha Karunarathna, and Sameera Suranjan learned how to set up bat detectors and identify different genera of bats from sound recordings, helping to build the capacity for long-term monitoring of bats on tea plantations and beyond.

Gather baseline data for multi-year bat monitoring

Bat activity data generated through this study will serve as baseline data for a multi-year bat monitoring program. Results were shared with the Forest Department, Department of Wildlife Conservation, and the tea industry in Sri Lanka.

Project conclusions

Using passive and active bat acoustic monitoring, Dr. Kusuminda and his research team established that Sri Lanka's tea agroecosystems support a rich and diverse bat population, including many insectivorous species that prey on nocturnal insects and tea pests. Study results highlight the potential for using bats as natural pest controllers in tea plantations.

The main recommendation is to develop an integrated pest management plan that includes installing bat houses to attract and support these beneficial bats, enhancing their role in controlling pests across different tea-growing regions.

To view Dr. Kusuminda's final grant report, including data, search our Publications section.