All product user guides can now be found at our brand new Knowledge Base.

Standing alongside the Yolo Causeway in central California, it’s hard to imagine that any animal could make this concrete behemoth their home. There’s nothing attractive about this 3.2-mile-long concrete bridge that elevates Interstate 80 above the Yolo Bypass, the floodplain for the Sacramento River. When you’re standing next to it, all you hear is the constant roar of cars speeding across the bridge.

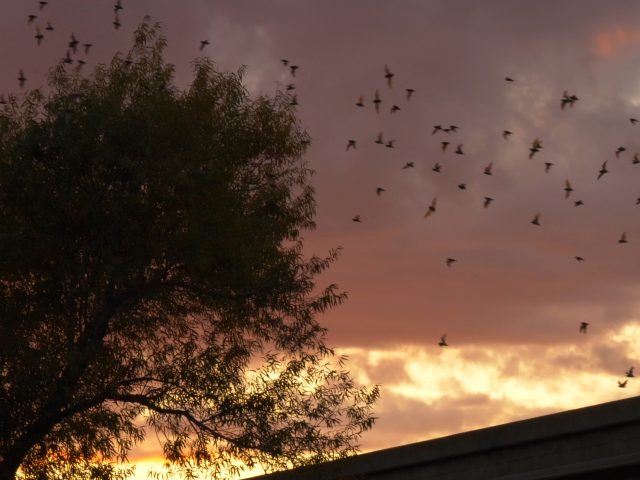

But as the sun starts to set, something magical happens. A quarter of a million bats begin to emerge from the causeway. At first you just see a few lone bats flying in the golden light of the sunset. Then, all of a sudden, waves of bats begin to emerge. Everywhere you look you see a seemingly endless sea of bats pouring out from underneath the harsh concrete of the causeway.

This is a sight that dozens of visitors get to witness when the Yolo Basin Foundation hosts its “Bat Talk & Walk” sessions, which are offered from June through September. It’s a stunning sight to see innumerable bats emerge from the causeway as semi-trucks roar past.

I’ve been a birder for the past 15 years. Bird watching gives me a reason to get outside and observe my surroundings in a different way. I pay attention to different details when I’m searching for a particular bird, and this elevates my experience in the outdoors. The first two documentary films that I made were focused on birds and bird conservation issues, and I spent the first part of my career working as a bird biologist.

When my colleague and fellow filmmaker Kristin Tièche first started telling me about her mission to make a feature documentary about bats and bat conservation, I knew almost nothing about this diverse group of animals. I knew that North American bats were in trouble, and I’d heard about the spread of white-nose syndrome, but as I learned more from Kristin I became more and more fascinated by bats. I learned that there is a whole community of bat enthusiasts and bat watchers – people who recreationally seek out and observe bats.

Over the last 15 years, I’ve watched as bird watching has evolved into an enormously popular and mainstream recreational activity practiced by millions of people. Birding tourism has become a huge industry, and this has changed the calculus behind lots of bird conservation efforts. We live in a capitalist society, so the establishment of a robust monetary incentive for protecting birds and their habitats is a game changer.

So as I watched Corky Quirk, the program coordinator for the Yolo Basin Foundation, sharing information about bats with an attentive group of bat watchers in front of the Yolo Causeway, I was imagining a world in which bat watching becomes just as popular as bird watching. This is one of the central goals of Kristin’s documentary, The Invisible Mammal – to introduce more people to the amazing and beautiful world of bats.

The bats that roost underneath the Yolo Causeway are Mexican free-tailed bats, and if you want to see them, there’s no better way than to join a "Bat Talk & Walk” session. But if you want to venture out to do some bat watching on your own, there’s some gear that you might want to become familiar with. Binoculars are a birder’s best friend, but they are less helpful for observing bats. Not only is much of your bat watching going to take place in the dark, but bats are constantly on the move. Instead of flitting from one branch to another and occasionally remaining stationary, most North American bats are in constant motion as they hunt for insects. It can be incredibly difficult to identify bats based solely on visual observation.

Enter the bat detector. Bat detectors are devices designed to detect the presence of bats by monitoring or recording their echolocation calls. Bat researchers have been using bat detectors for a while, but recently this technology has become a lot more accessible. A few years ago Wildlife Acoustics changed the game when they started selling a bat detector that plugs into a smartphone and is capable of recording calls and identifying different bat species.

Kristin and I got to see this technology in use when we visited Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge outside Fallon, Nevada with one of the characters in The Invisible Mammal, bat researcher Dr. Kristin Jonasson. She explained to us that when she needs to unwind and release stress, she goes bat watching – and this was one of her favorite spots.

We were treated to an amazing sunset at the Refuge, and just as the sun dropped below the horizon, the bats started to emerge. Although not nearly as dramatic as watching a quarter million bats emerge at once, bat watching at Stillwater was amazing in a different sort of way. There was a diversity of different bat species present, and sure enough, Dr. Jonasson pulled out her bat detector and began pointing it at individual bats as they flew by. She excitedly called out species names to us as her phone screen displayed the identification data for the bats we were watching.

Soon it was too dark for us to continue filming, but the bats continued to encircle us and it was exhilarating! I felt the same excitement that I feel when I spot a rare bird, or identify a species that I’m seeing for the first time. Now that I’ve felt that excitement, I want to share it with my fellow birders, and I know that Kristin’s film will help inspire more people to get out and experience the joy of bat watching!

Matthew Podolsky is the producer of the upcoming feature documentary, The Invisible Mammal. To learn more about the film, or to make a donation, please visit theinvisiblemammal.com.